Photo Credit: Scott Webb

In part 1 we discussed what researchers have found to be the top risk factors to low back pain. Quick summary: poor trunk stability results from muscle imbalances which excessively challenge the surrounding muscles and structures that support us. When it comes to explaining low back pain, it helps to break the anatomy down in 3 basic areas. All of these 3 components marinate together in order to provide us with all the stability necessary to function well.

First off, bones and ligaments are the basic "foundation posts" of our body. They provide basic and important stability to our whole body. Self evident that without our vertebrae and ligaments, we'd be in a whole lot of trouble. Secondly, muscles that surround the spine provide the most stability. Our trunk muscles need to demonstrates both power and endurance in order to provide stiffness at each segment of the spine. Muscle endurance become especially important in order to carry out prolonged and stressful activities such as running. Lastly, neural control is undoubtedly crucial for spine stability because our bodies need to be able to not only properly active our trunk and spine muscles but our nervous system needs to beautifully coordinate muscle activity and timing appropriately to expected and unexpected forces (1,2). If all of these 3 components work as they should, there is a very high change that you will be able to compete and train with a lower likelihood of developing any low back injuries.

Usually for someone to develop back pain, there tends to be a deficit in more than one of these areas mentioned above. A common one being, poor motor control or poor muscle strength and endurance lead to excessive load on the tissues causing pain, especially after prolonged and repetitive stresses.

So how do we correct deficits and improve function and pain? A lot of research has looked into exercise and training and its affects on pain and function. In a 2004 review of articles, the authors concluded that exercise helped decrease pain in improve function, so that is GOOD news for us active people- more exercise ! :) (3,4,7)

In my clinical opinion, I try to remind my athletes that in order for you to run and stay pain/injury free you have to be fit. Running is not easy on the body, I have previously stated that the body has to tolerate 3x our weight each time out foot touches the ground. That means our joints all the way from our neck down to our ankles have to stabilize our heavy limbs each step of every mile.

So let’s tackle each of the 4 contributing factors of back pain (I presented in Part 1 of this blog series) with some exercises you can implement.

Deficit #1: Weak Lumbar Extensors

According to McGill norms for trunk extensor endurance for males is about 161 seconds and for females 185 seconds, plank norms for athletic men 120-180 seconds and athletic women 90-120 seconds, and side planks 60-90 seconds for athletic men, and 75-86 seconds of athletic women. Therefore, if you find that you are not even close to these norms- you should work to get there!

The muscle we are targeting here are the multifidus and quadrates lumborum.

1. Bird-Dogs:

- Get into a quadruped position: hips over knees & shoulder over hands

- Begin by tightening core, keeping spine neutral (avoid rounding or arching)

- Extend one arm and opposite leg outward simultaneously- MINIMIZE trunk rotation.

2. Side-Plank:

- Lay on your side- onto your elbow - place the top foot onto of the bottom foot and straighten both legs

- Engage core and Lift your body off the ground- there are only 2 points of contact, your elbow /forearm and the side of the bottom foot

- Hold - 30 seconds bouts

3. Supermans :

- While lying face down, slowly raise your arms and legs upward off the ground. - keep your chin tucked- hold for 5 seconds

- Then lower slowly back to the ground- you will feel your lower back work!

- bouts of 1min x 3

Deficit #2: Delayed Activation of the Transversus Abdominis.

Many studies focus on the just the Transversus Abdominis (TrA), which is true it is dysfunctional in patients with low back pain. I will throw in here that many times it involves the obliques, and the diaphragm.

Before you even begin progressing exercises for the abdominals I HIGHLY recommend working on Diaphragmatic Breathing and proper Core Engagement- and this my friends is NOT EASY, particularly for those who are new to consciously thinking and operating properly through activities they have taken for granted. Correct exercise follow below:

Diaphragmatic Breathing: ( creating intra-abdominal pressure IAP)

- Start off laying on your back with your knee bent or sitting.

- Cup the side of your trunk with both hands or use a belt.

- As you inhale think about filling your abdomen and filling the whole abdominal cavity; you can also try to think about pushing your stomach in all directions as you inhale- you should feel both thumbs and fingers being pushed out.

- Gently exhale with lips pursed to create tension and repeat.

Sahrmann Core Exercises Level 1,2,3

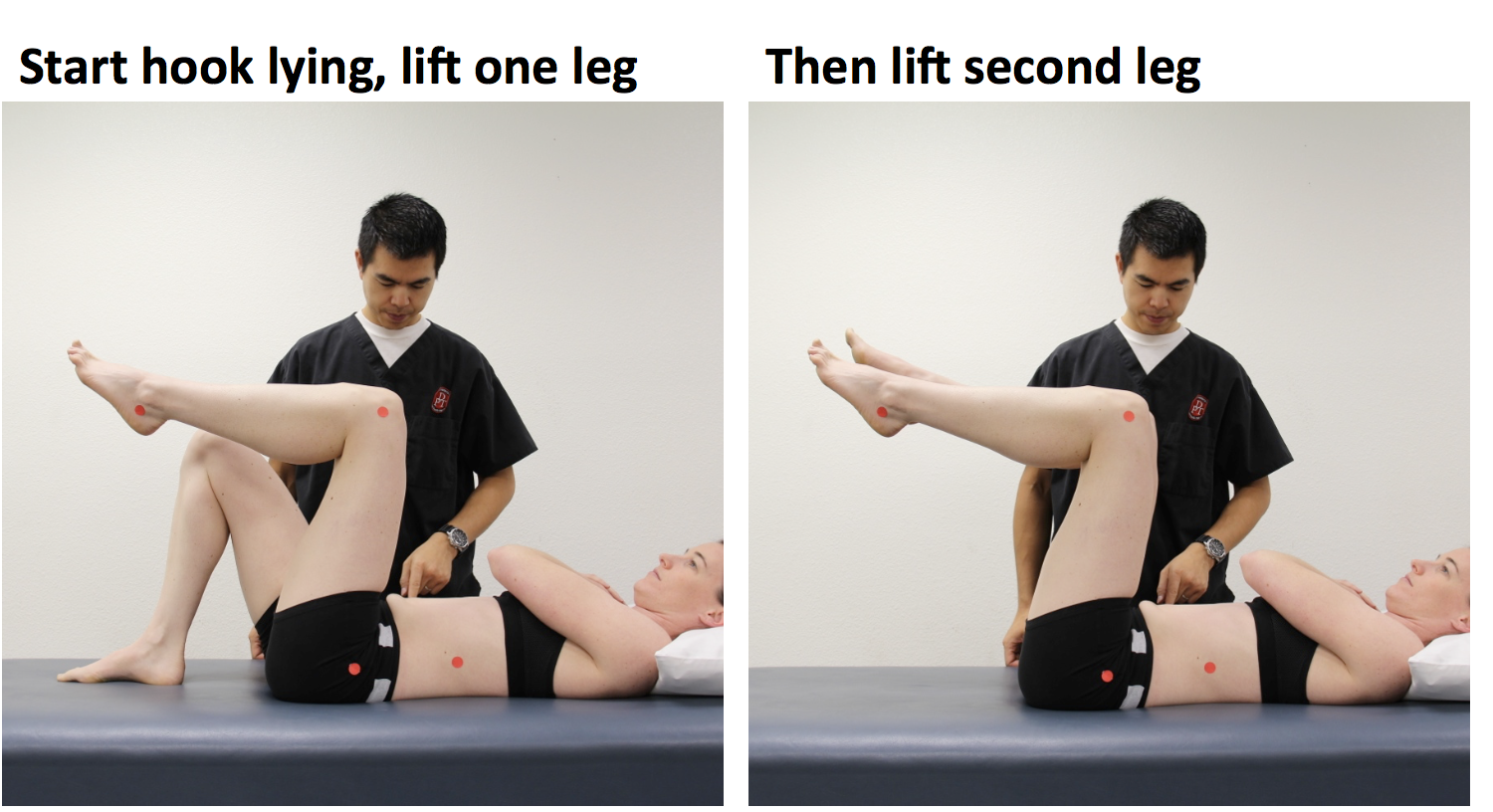

Level 1:

- Lay on your back with knees bent, low back flat against the ground , ribs tucked down

- engage core- and without arching back lift one leg into the air followed by the next

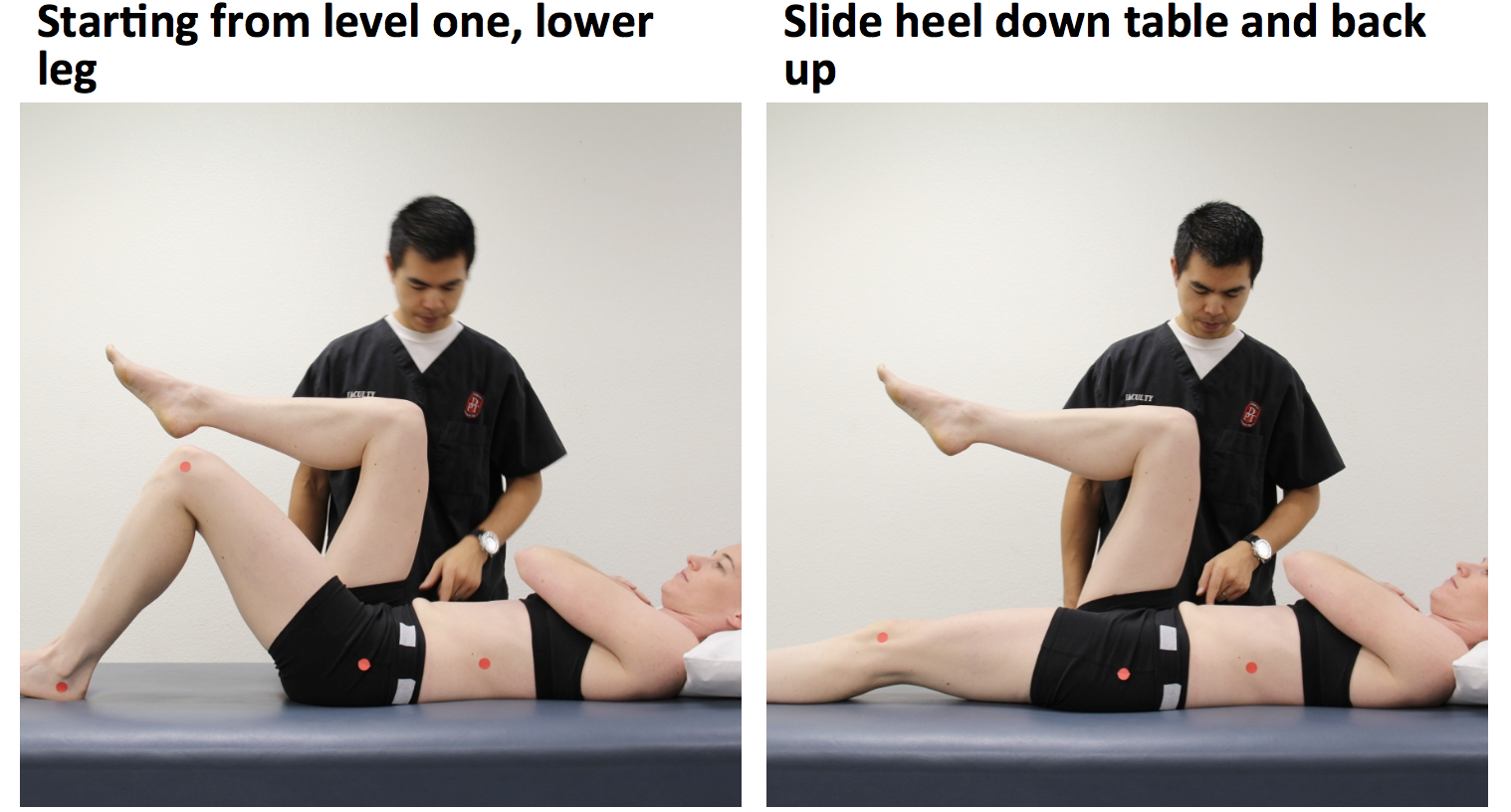

Level 2:

- Start out with both legs floating in the air at 90 deg

- engage core, without arching back bring one leg down and slide it out and slide it back in and switch

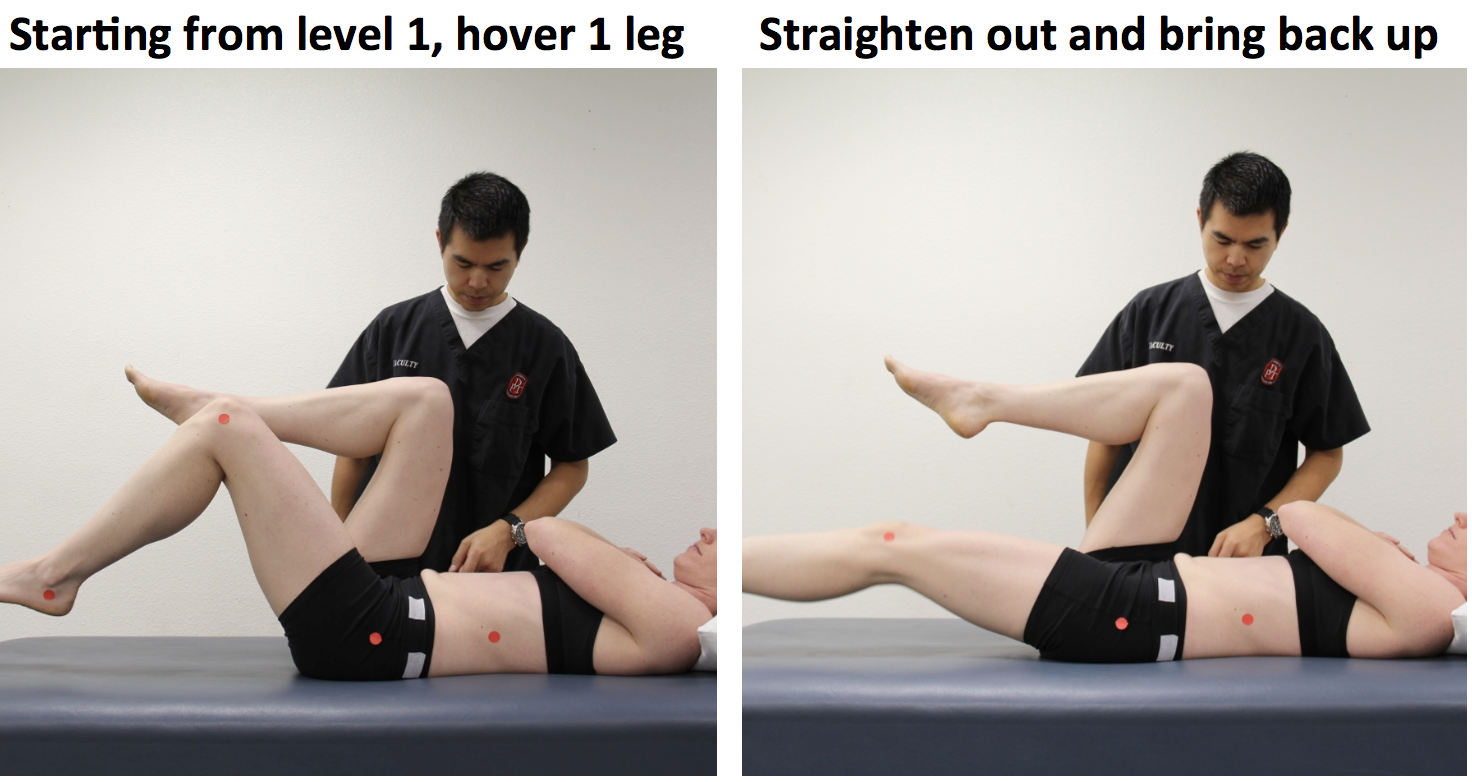

Level 3:

- Start out as in level 2

- this time instead of sliding a foot out, you will float the whole leg out.- WITHOUT arching the low back or flaring the ribs.

all done until fatigue- or break down of form. You should NOT feel your low back working/burning.

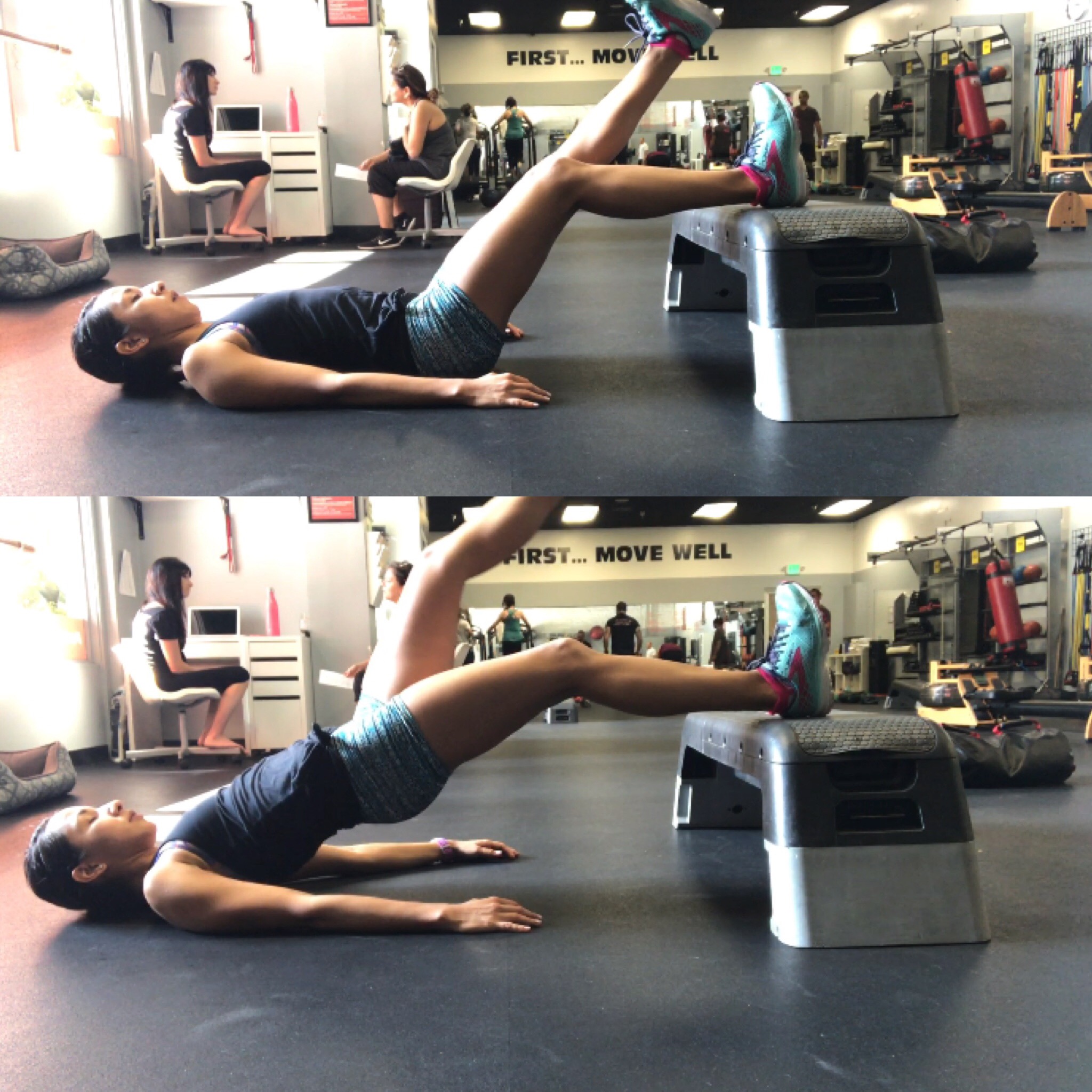

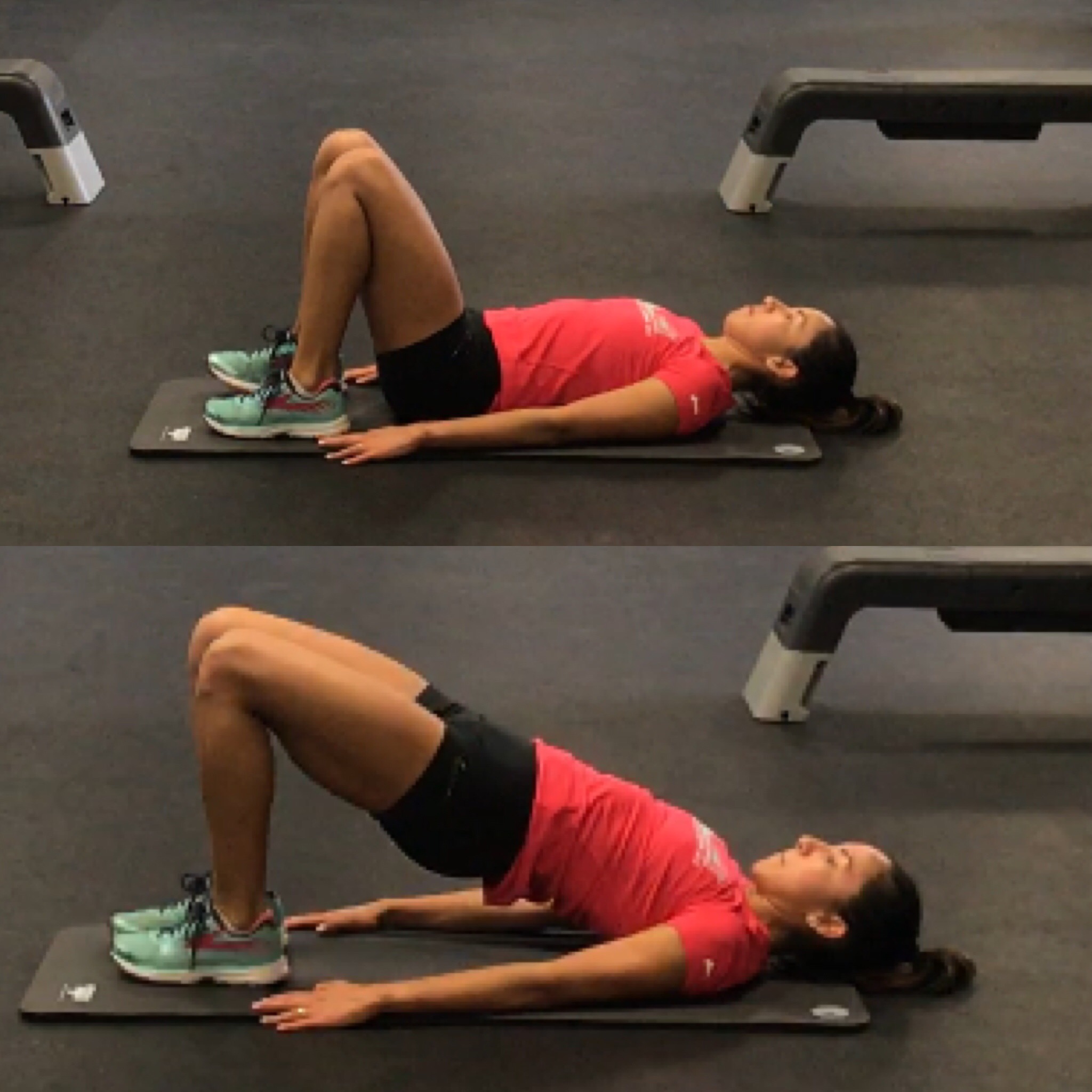

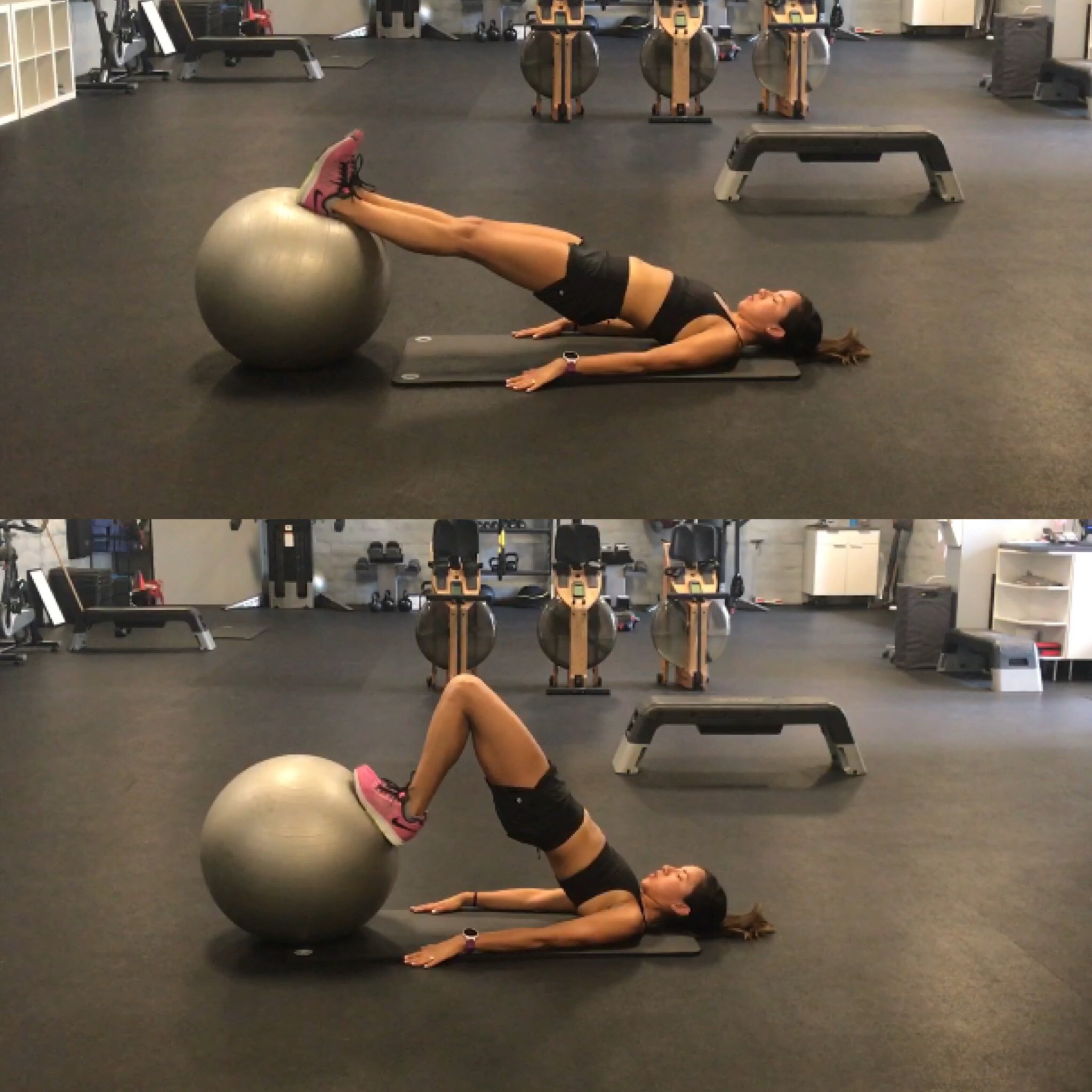

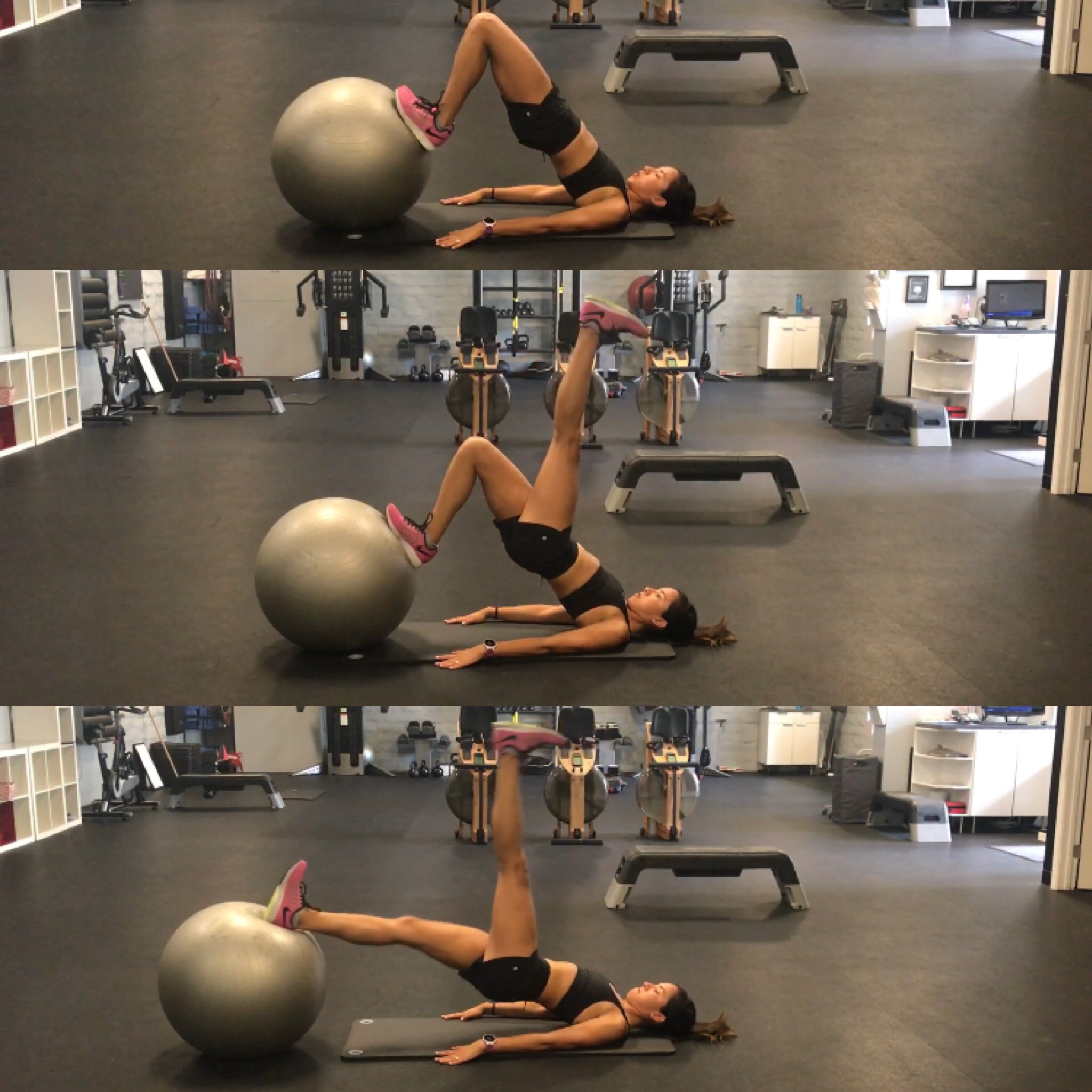

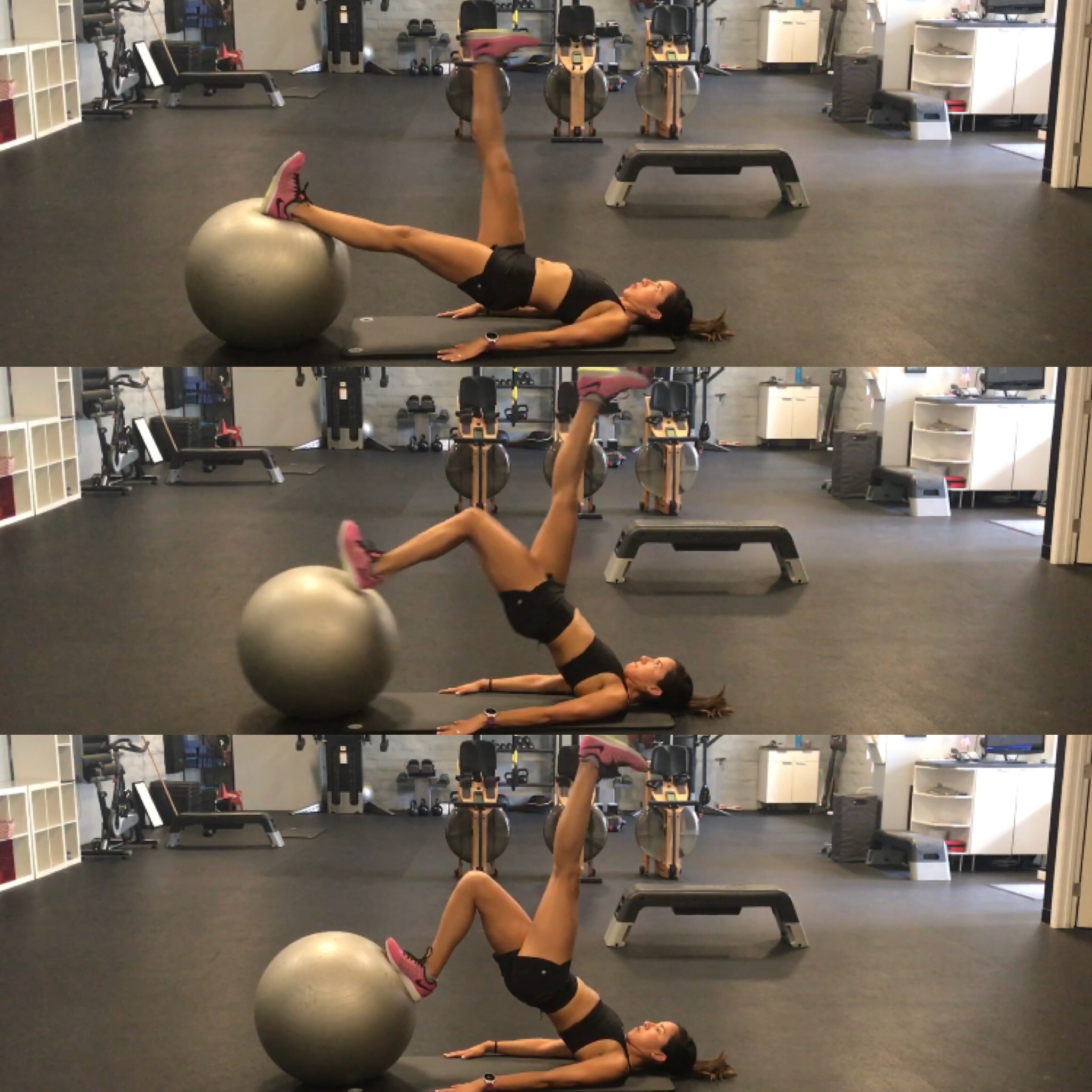

Deficit #3: Weak Gluteus Maximus:

The GLUTES!!! The mighty glutes. Yes, you would be surprised as to how many runner DO NOT incorporate staple glute exercises. Our hips are what are suppose to power us forward. If anything we do need strong glutes as well as strong hamstrings and calves. For the most part, it is more common to see over dominant hamstring vs over dominant glutes. Having strong gluten will also help reduce some hip flexor stiffness because powerful hip extension will promote less pull from the leg.

When you start doing exercises: you have to progress from non-weight bearing exercises to weight bearing exercises.

Non Weight bearing:

Clam

- For both versions- you will use a theraband for resistance- place around the knees

- Get into a sidling position and slightly role the whole body forwards

- Keep your heels together and lift the top knee towards the ceiling- make sure you feel the gluteus burn after a few repetitions- NOT the side of your leg/quad/back/or hamstrings.

- Advanced- Clam with Side-Plank ( see side plank bone and add Clam movement)

Non-Weight Bearing:

Squat with Band

- Place band around knees- stand shoulder width apart- and push band apart

- Begin to squat down- thinking about sticking hips out as if reaching far back for a chair

- Maintain the tension of the band around the knees by pushing as as you squat down

Firehydrant: ( really difficulty exercise FYI, need good balance and core strength)

- Place band around the knees, and balance on one leg

- Hinge through the hips- stick butt out and slightly bend the loaded leg

- Engage the core and slowly rotate floated knee out towards the side

- DO NOT LET trunk or hips rotate-

- Hold for 1-2 seconds and slowly return to the start and repeat

Deficit #4: Stiffness of Hip Flexors:

The hip flexors role are to bring the knee up. As runners we do this thousands of times. A lot of runners will have some sort of stiffness. Some more than others, and if your hips are too stiff it will create an anterior pelvic tilt and result in increase stress at the low back.

Stretching your hips along with implementing hip extension exercises as demonstrated above will help keep everything as balanced as possible.

The one stretch I always teach is the kneeling hip flexor stretch.

The trick to this is tucking the hips before leaning forward!

Kneeling Hip Flexor Stretch

- Get in kneeling position

- brace core and tuck your butt/hips under

- Gently lean forward with your hips first

- hold for 15 sec and back off total of 2 min per side.

Summary:

- Recall that usually if you are having back pain, the cause will most likely be a combination of deficits if more than 1 area!

- If your back pain is getting worse and affecting your training and performance see your local Physical Therapist - and get going on the right path.

TRAIN SMART, RUN HAPPY

-Your fellow runner,

JESSICA MENA PT, DPT, CSCS

Doctor of Physical Therapy

Blog edit: Amir Medovoi

REFERENCES:

1. Barr KP, Griggs M, Cadby T. Lumbar Stabilization Core Concepts and Current Literature Part 1. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2005 June

2. Barr KP, Griggs M, Cadby T. Lumbar Stabilization A Review of Core Concepts and Current Literature Part II. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2005 June

3. Gomes-Neto M. Lopes JM, Canceicao CS< Araujo A, Brasileiro A, Sousa C, Carvalho VO, Arcanjo FL. Stabilization exercise compared to general exercise or manual therapy for the management of low back pain: A Systematic review and meta analysis. Journal of Physical Therapy and Sports. 2017 Jan 23; 126-142

4. Hicks GE, Elvira JL, Delitto A, McGill SM. Preliminary development of a clinical prediction rule for determining which patients with low back pain will response to a stabilization exercise program. Arch Phys Med and Rehab, 2005. Sep: 86(9)

5. . HodgesP,CresswellAG,DaggfeldtK,ThorstenssonA. Preparatory trunk motion accompanies rapid upper limb movement. Experimental Brain Research. 1999; 124.

6. Hungerford B, Gilleard W, Hodges P, Evidence of altered lumbopelvic muscle recruitment in the presence of sacroiliac joint pain. Spine. 2003;28:1593-1600.

7. McGill SM, Karpowicz A. Exercises for spine stabilization: motion/motor patterns, stability progressions, and clinical technique. Arch Physical Med Rehabil. 2009 Jan;90(1):118-26. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.06.026.