Hamstring strains are a common lower extremity injury and it involves a strain or tear of 1 or 3 of the hamstring muscles or tendons. The hamstring is made up of three muscles. The semitendinosus, the semimembranosus, and the biceps femoris muscle. They originate on the sit bones, otherwise known as the ischial tuberosities and run down the back of the leg, cross the knee and attach to the inner and outer part of the lower aspect of the knee.

Hamstring strains commonly happen when there is an excessive force placed across the muscle, typically seen with sprinting, sudden start/stopping motions, jumping, hurdling, and heavy lifting. During running a strain occurs during the eccentric contraction of the muscle, or when the hamstring elongates during the late swing phase (phase when you are swinging your leg forward and the knee straightens and reach out with the foot up to right before the foot touches the ground) (1-7).

Unfortunately, there is a high injury reoccurrence rate that averages 31% over a sport season with the highest likelihood within the first 2 weeks of return to sport (3).

Hamstring strains are categorized as Grade I, II, and III strains.

Grade I : mild strain injury with minimum tear of the musculotendinous unit and minor loss of stress

Grade II: moderate strain injury with partial tear of the musculotendinous unit and significant loss of stress which results in significant functional limitation.

Grade III: severe strain injury with a complete rupture of the musculotendinous unit and is associated with severe functional disability (5).

In running the most common grade of injury are grades I and II.

Hamstring Strain Risk Factors:

Understanding the risk factors for hamstring injuries is really important in developing training programs in order to tackle these deficits. There has been an abundant of literate to support the finding of these traits largely contributing to hamstring strains.

1. Hamstring stiffness- With any muscle there has to be balance in length and strength. When an overused muscle also presents short and tight it cannot generate maximal force. Therefore, when large amounts of work are required, the muscle is essentially forced to contract even more causing injury. Heiderscheitexplains that after a strain hamstring length is really limited, normal flexibility of the hamstring should allow the leg to flex forward 80 deg with the knee straight (2).

2. Hamstring strength and endurance deficits: In a study conducted by Orchard et al, they found that 30 players with hamstring injuries demonstrated significant lower hamstring strength than that non-injured counterparts.

Researchers also found that strains would occur during late portions of practices and competitions. This means that poor muscle endurance led to excessive fatigue, poor energy absorption, and decreased work output leading to injury (3).

3. Poor warming up prior to a work out or competition- increasing muscle temperature increase the muscle length. Physiological tests of muscles and tendons have shown that tissues that were “preconditioned” (stretching prior to testing force to failure) tolerated greater amount of stress before tissue deformity/tearing to the tissues that were not stretched prior. (4)

Signs and Symptoms You Strained Your Hamstring:

Treatment:

Recent proposed rehabilitation guidelines are divided into 3 phases. (5,2)

Phase I: 1-7 DAYS

· The focus after a strain is to control inflammation, swelling, and bruising. ( P.O.L.I.C.E)

Protection

Optimal Loading

Ice

Compression

Elevation

Pigeon Pose Glute Squeeze

· Excessive stretching should be AVOIDED, but very gentle pain free range of motion is encouraged. Pain free single leg balance exercise, short stride stepping drills, isometric glute exercises are good exercises to carry out during the acute phase of a strain. Avoid resistance training of the hamstring muscle. Usually if there is a movement coordination discrepancy, such as an over dominant hamstring vs. increase glut activation you may begin working on coordination here.

- Examples of coordination exercises: prone glute contractions, pigeon pose glute squeezes with knee extensions.

· In order to move on to phase 2, you should: be able to walk normally without pain, be able to jog very slow without pain, and be able to hold and isometric hamstring curl to 50-70% of submaximal strength without pain.

Phase II: 7 DAYS TO 3 WEEKS

· Return to full range of motion is a goal, and a gradual increase of exercises of:

- BALANCE: Y- balance, unstable surface

- AGILITY DRILLS: ladder drills

- CORE EXERCISES.

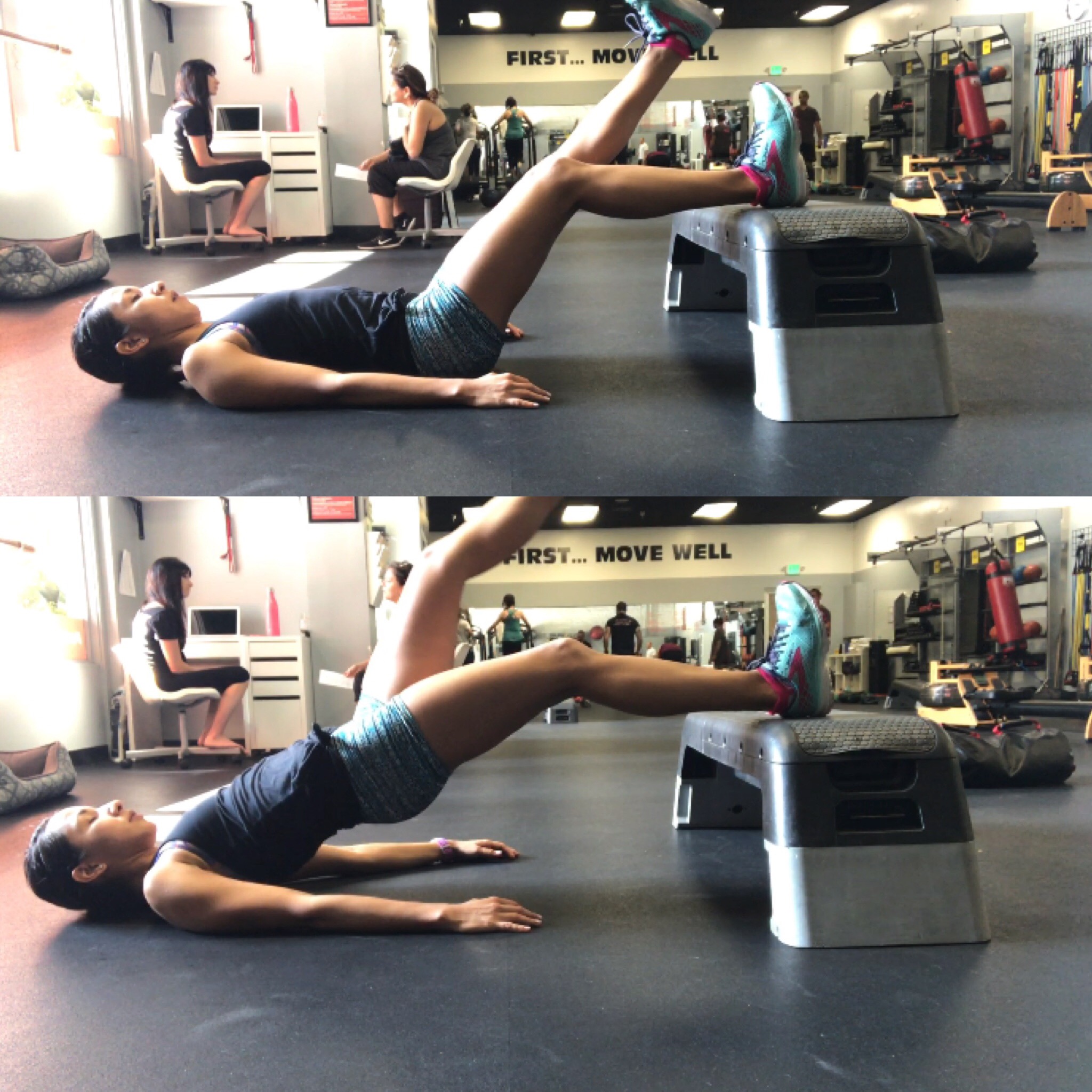

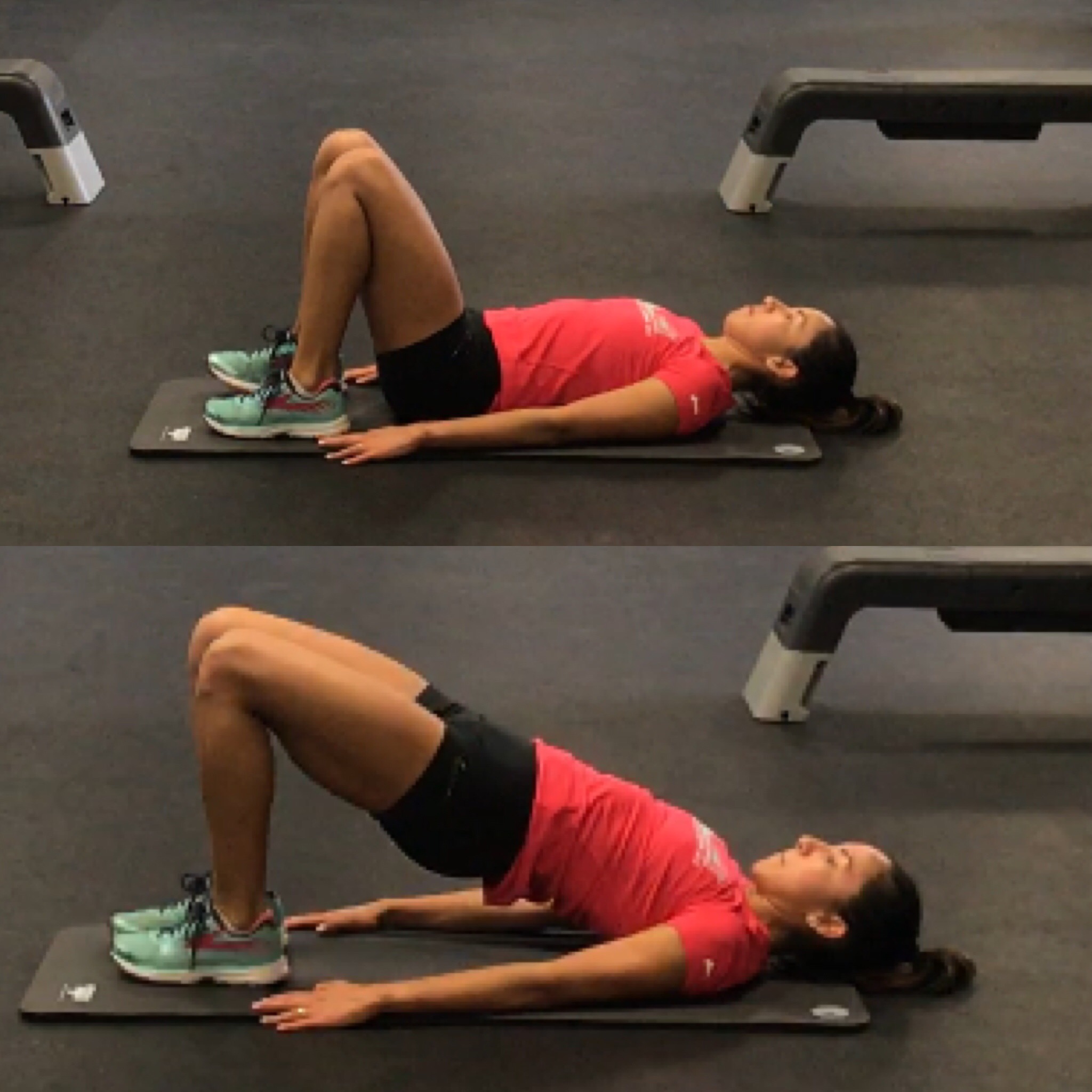

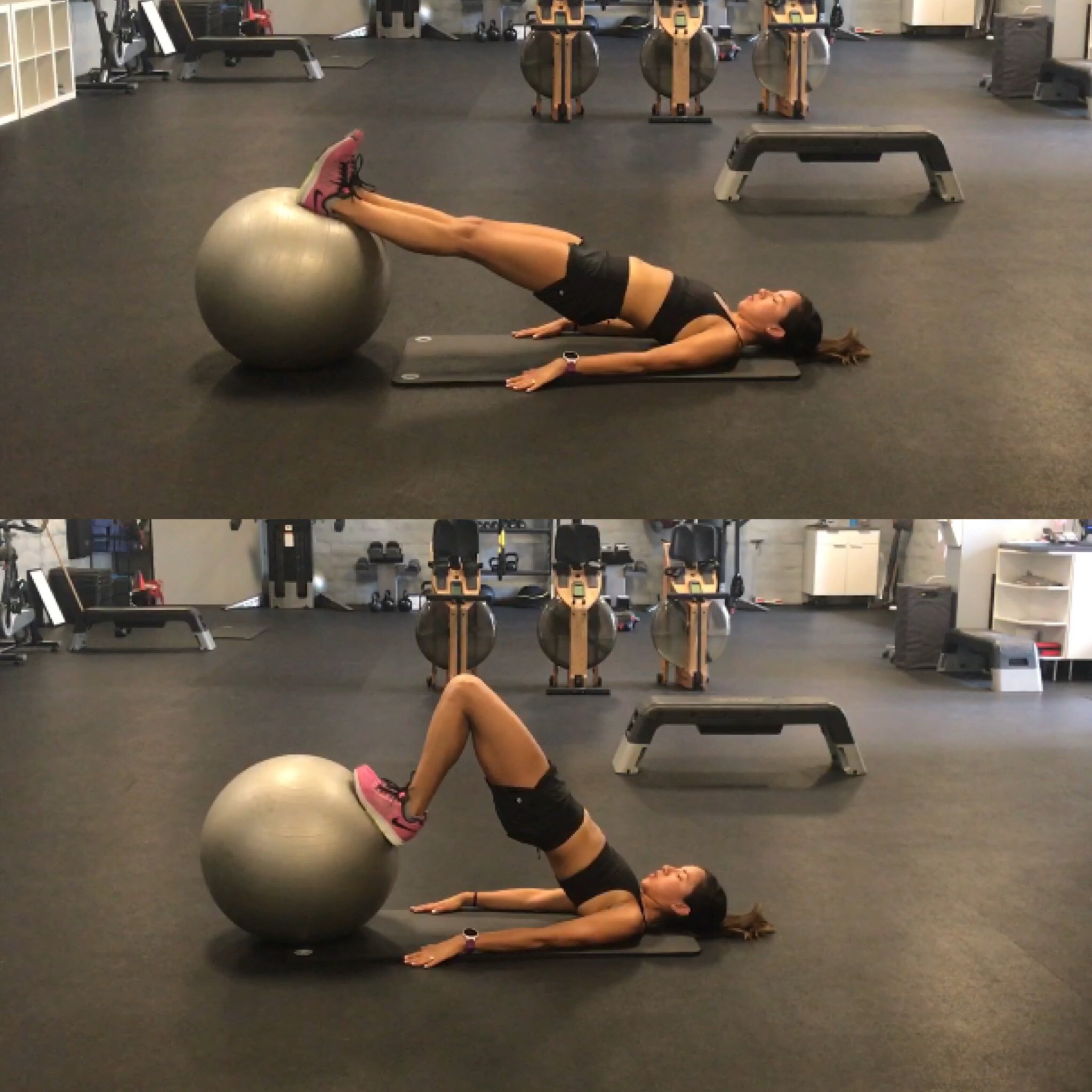

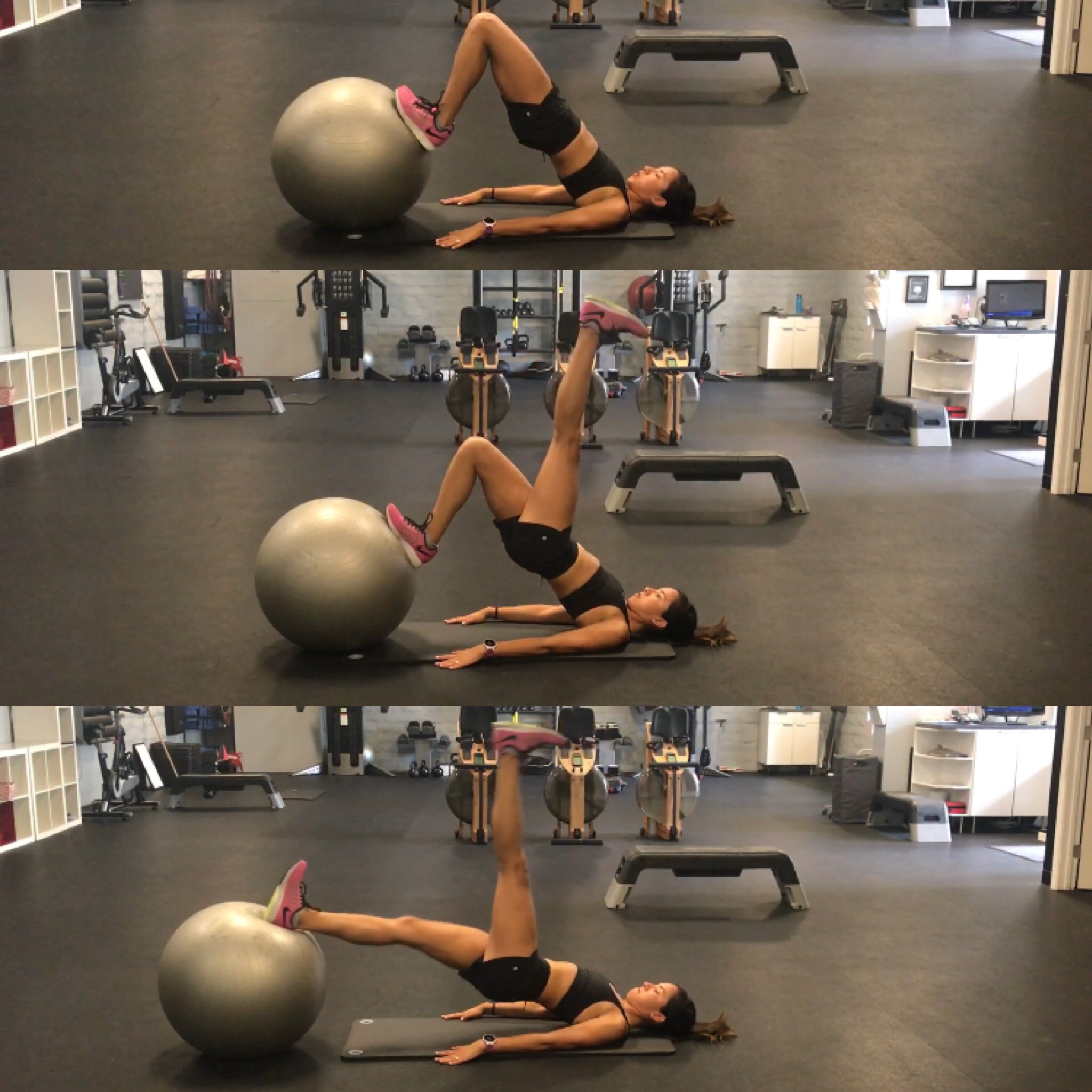

· Begin gentle eccentric (lengthening) hamstring strengthening not concentric (shortening). You should be able to perform a bridge walk out in preparation to the next phase of return to sport.

· In order to move onto phase III you must be able to: demonstrate full strength without pain, be able to jog forwards and backwards at 50% of your maximal speed without pain.

Phase III: 1-6 WEEKS // can last up to 6 month for complete ruptures.

· Hamstring flexibility should be back to 100% normal.

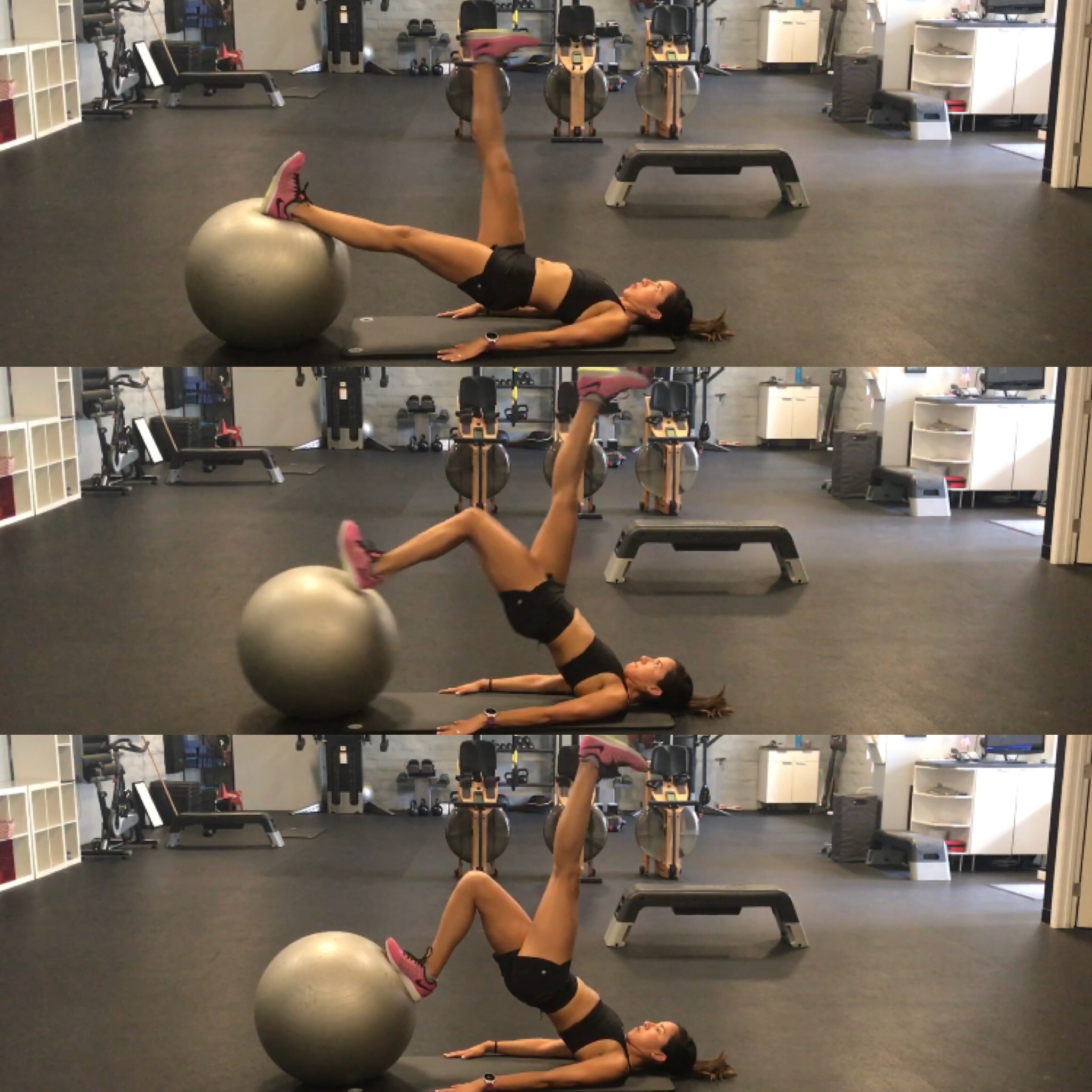

· Progress eccentric and concentric hamstring strengthening with no pain.

- Example: ( See picture bar below):

- Bridges

- single leg bridges

- Single leg Russian deadlifts without and with weight,

- walking lunges, walking lunges with rotations.

- Sprinters will begin quick takes off and breaks, runners will begin leg turn over exercises, farklegs, short distance bursts ONLY when you have been able to carry out all exercises WITHOUT PAIN.

SUMMARY:

Grade II and III hamstring strains will take time to heal! Patience is key and being smart about strengthening will be far more beneficial in the long run. Doing things the right way without rushing will only limit the chances of another reoccurring strain to occur.

TRAIN SMART, MOVE WELL, AND GET BACK OUT THERE

- Jessica Mena PT, DPT, CSCS

REFERENCES

1 Erickson L.N, Sherry M.A. Rehabilitation and Return to Sports After Hamstring Strain Injury. Journal of Sport and Health Science. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2017.04.001

2 Heiderscheit B.C, Sherry M.A, Silder A, Chumanov E.S, Thelen D.G. Hamstring Strain Injuries: Recommendations for Diagnosis, Rehabilitaton, and Injury Prevention. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 2010 40: 2

3 Lui H, Garett W.E, Moorman C.T., Bing Y. Injury Rate, Mechanism, and Risk Factors of Hamstring Strain Injuries in Sports: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Sport and Health Science. 2012 V: 1:2https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2012.07.003

4 Mair S.D, Seaber A.V,. Glisson R.R, Garrett W.E. The Role of Fatigue in Susceptibility to Acute Muscle Strain Injury. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 1996 pp. 137-143

5 Petersen J, Holmich P. Evidence Based Prevention of Hamstring Injuries In Sport. British Journbal of Sports Medicine 2005;39:319e23.

6 Safran M.R., Garrett W.E.J. , Seaber , . Glisson , .Ribbeck B.M.. The role of warmup in muscular injury prevention Am J Sports Med, 16 (1988), pp. 123-129

7 Yu B., Kiu H, Garett W.E. Mechanism of Hamstring Muscle Strain Injury In Sprinting. Journal of Sport and Health Science. 2017 Vol 6: 2 pg: 130-132 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2017.02.002